A crucial decade lies ahead for the oil and gas sector to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. Our Net Zero blog series explores the priorities, challenges and opportunities as climate change dominates boardroom conversations.

The 1960s ushered in the natural gas age. In homes around Britain, some 20 million domestic appliances were adapted or replaced to use natural, rather than manufactured, gas over a decade. Sixty years on, the world is in the middle of another energy revolution, and one unlike any other before. This transformation has been brought about by the need to halt climate change. It is being propelled by market forces across the oil and gas supply chain, as consumers, investors and other stakeholders increasingly demand low-carbon solutions. It is driven by a plethora of growing regulations, schemes, standards, recommendations and guidance, globally. And time is of the essence. As Tim Eggar, Chairman of the Oil and Gas Authority (OGA), remarked: “Industry’s social licence to operate is under threat and there is no scope for a second chance.”

CO2 accounts for the majority of gaseous emissions from offshore installations, mobile offshore drilling units (MODUs) and supply vessels. Around three quarters of these emissions are from the direct combustion of fossil fuels for power generation. Flaring of gas at installations is the other main source; an activity which, alongside venting, also produces potent methane emissions.

Four challenges

Ahead of the UK holding the next UN Climate Change Conference (COP26 in late 2021), OGA has challenged the industry in four key areas:

- Commit to clear measurable greenhouse gas targets, with real progress on methane

- Show progress on carbon capture and storage, including work having started on major projects

- Demonstrate measurable progress on energy integration opportunities – for example, an electrification project

- An acceleration of the move to ensure there is a diverse array of skills and people for the long-term energy offshore and supply industry

Three opportunities

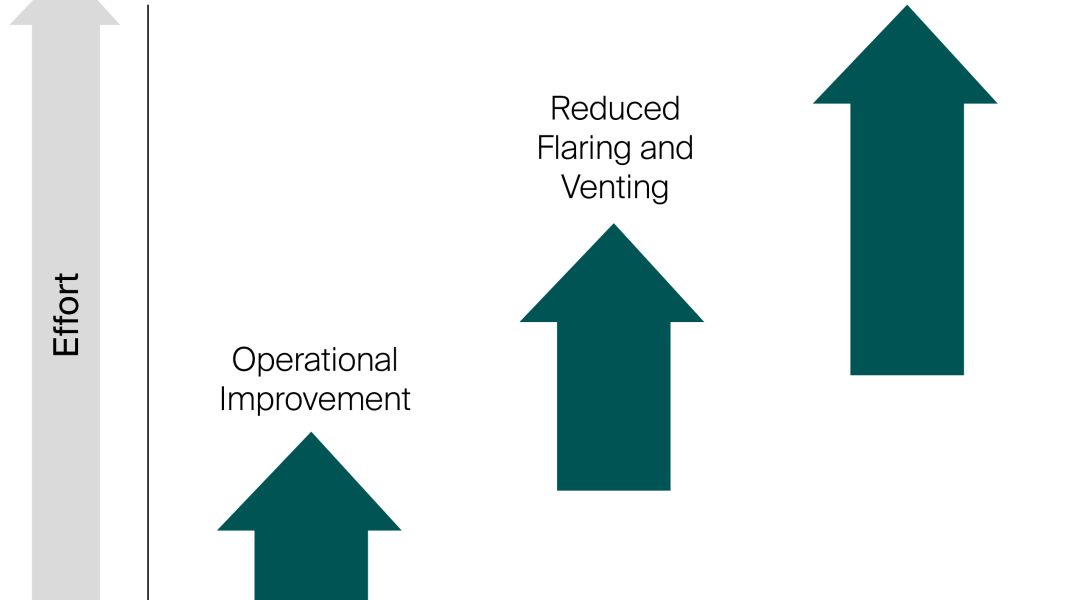

The OGA has identified three primary means of reducing upstream emissions, plotted along an ‘abatement potential curve’: making operational improvements, reducing flaring and venting, and introducing step-change emissions reduction (see fig. 1).

Fig 1. The route to emission reductions and scale of opportunity (abatement potential).

We’ll be exploring each of these opportunities in our Net Zero blog series, starting by setting realistic targets and a clear baseline for operational improvements. There will be no real progress without completing this essential task first. We’ll be arguing for consistency when it comes to environmental reporting and the need to set boundaries – asking what’s in and what’s out? – before attempting to calculate an organisation’s carbon footprint. Having a transparent benchmark across an organisation’s supply chain is also fundamental when reducing flaring and venting emissions. We’ll also be looking at new and emerging technologies for transforming the UK Continental Shelf into a Net-Zero basin by 2050 and the changing market landscape. In particular, the convergence of Carbon Capture Storage and blue hydrogen production to heat homes and workplaces could be a potential Net-Zero game-changer, transforming ‘waste management’ into a lucrative new business.

While new businesses and technologies will make the headlines, for many organisations the focus will be on scoping Net Zero based on commercial priorities. Key factors for existing operations will be asset location, age and maturity; production process and potential; remaining field life; and the lifetime projection of emissions. A large and largely untapped area to date is adopting an integrated approach to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions management. Several ISO standards now share the same architecture and elements, so management systems can effectively ‘talk to one another’. This offers an effective way to make a positive difference on emissions reduction and shouldn’t be underestimated.

In context: Key legislation

The Paris Agreement sets out a global framework to avoid dangerous climate change by limiting global warming to well below 2°C (above pre-industrial levels) and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature even further to 1.5°C. The Agreement requires all parties to put forward their best efforts through nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and strengthen these efforts moving forwards.

In the UK, through the Climate Change Act 2008, the government introduced a long-term, legally binding 2050 target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 80% relative to 1990 levels. It also introduced ‘carbon budgets’, capping emissions over successive five-year periods (set 12 years in advance) and the need for a UK Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA), again every five years. This Act also gives powers to the UK government to require certain organisations to report on how they are adapting to climate change (under a special ‘adaptation reporting power’). The scope is broad-ranging, covering drilling contractors, exploration and production companies, joint ventures and the supply chain.

There is a similar picture worldwide, where governments have established agreed NDCs.

Related Services